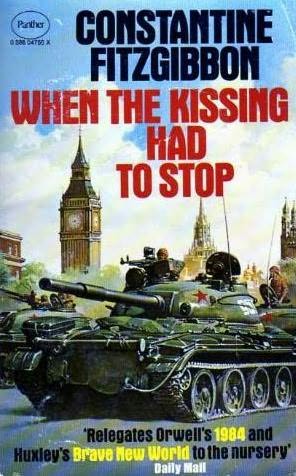

When The Kissing Had To Stop was published in 1960, and republished in 1980, which is when I first read it. It’s a book set in the near future of 1960, clearly intended as a warning “if this goes on” type of story, about a Britain taken over by a Soviet plot aided by a few troops and some gullible British people, much as Norway was taken over by Hitler in 1941 and Tibet by China in 1959. (Russia never in fact used that kind of tactics.) It’s written in a particularly omniscient form of bestseller omni, it has a large but consistent cast of characters, and many of the chapters consist of such things as saying what they were all doing on Christmas Eve. The characters are very well done, there are Aldermaston Marches (cynically funded by Russia for their own ends) there’s a coup, and by the end all the characters except one are dead or in gulags. I think I’ve always read it through in one sitting, sometimes until very late at night, it’s not a book where it’s possible for me to sleep in the middle.

Re-reading this now, I’ve just realised that this was a very influential book. I’m not sure if it was influential on anyone else, indeed, though my copy quotes glowing reviews from the British mainstream press, I’m not sure if anyone else ever read it at all. But it was very influential on me, and particularly in the way I wrote about people going on with their ordinary lives while awful things happen in the Small Change books. Fitzgibbon does that brilliantly here, they’re worrying about who loves who and whether to get a divorce and all the time the Russians are coming. He also keeps doing the contrasts between upper-class luxury and horror—from carol singing in a country house to carol singing in the gulag, from the Kremlin plotting to champagne at the opera.

This isn’t a subtle book, and it isn’t really science fiction—it was clearly published as a mainstream book. Fitzgibbon tries harder than most mainstream writers of Awful Warnings to do extrapolation. The Irish lord who works in an advertising agency and who is one of the more significant characters is working on a campaign for “fuelless” atomic cars. Otherwise, he has extended the trends of the late fifties forward without actually coming up with any of the actual developments of the sixties. They’re getting a Russian invasion and atomic cars, but they are listening to big band dance music and they have teddy boys. This isn’t a problem. He tried, and it feels like a reasonable 1960 anyway.

It isn’t a cosy catastrophe, but it does have some things in common with one. First, there’s a catastrophe, though all the book leads up to it. Second, all but two of the characters are middle- or upper-class—and those two are very minor, a black American soldier and his Cockney girlfriend. All the others, including the defector who returns briefly from a gulag, are very definitely of the ruling classes. The omniscient narrator says that the working classes have been made just as comfortable and have a high standard of living—but we see lots of servants, and lots of riots and discontent. The main difference is that nobody survives—but a lot of the characters are quite unpleasant, in quite believable ways. The positive characters tend to die heroically, and as for the others, I’m delighted to see some of them get to the gulag. There’s a strong flavour of “they got what they deserve” about this book, even more than “it could happen here.” And there’s a huge stress on the cosiness of luxury and alcohol and country houses and Church on Sunday.

We spend most time with Patrick, Lord Clonard, who works in advertising, helps the CIA, and worries about his love for the actress Nora May. Nora isn’t really a character, we see very little of her point of view. She’s married with a son, but having an affair with Patrick. Her sister, the novelist Antonia May, drags Nora into the anti-Nuclear movement. Antonia is really obnoxious. She has a lovely body but an ugly face, she doesn’t like real sex and she’s pitifully in love with the politician Rupert Page-Gorman—my goodness, his name is enough. Page-Gorman is shown as cynically manipulating the people. He started as a Conservative MP and crossed the floor to Labour when he saw he could do better there. (Did you know Churchill started off as a Tory, crossed to Liberal, became an independant and then ended up back with the Tories?) The Russians, whose inner councils we see, are shown as just as cynical, barely paying lip service to their supposed ideals. The other politicians on both sides are shown as indecisive and narrow of vision—except for Braithwaite, who is genuine and stupid and totally conned by the Russians.

There’s one very odd and interesting character, Felix Seligman. He’s a financier. (Stop cringing.) Felix is an English Catholic of Jewish ancestry. He’s portrayed as genuinely generous, hospitable, loyal, brave and patriotic. He’s also the only character to survive out of the camps—he ends up as a notorious guerilla leader in Wales. (He spent WWII in the Guards.) He’s also surprisingly civilized to Nora, even though she doesn’t love him and is having an affair with Patrick. He loves their son, and traditions, and he’s the only person in the whole book who is entirely uncompromised. Yet though Fitzgibbon is bending over backwards to avoid anti-Semitism, he does give Felix an instinct (which he doesn’t obey) which he inherited from his ancestors who used it to get out of Russia and then Germany in time. And he is a financier and he does get a large part of his money out of the country through loopholes—not that it does him or his son any good as things turn out.

Fitzgibbon himself had an interesting background. His father was of the impoverished Irish aristocracy, and his mother was an American heiress. He went to Exeter College Oxford in 1938, and joined the Irish Guards when WWII began in September 1939. When the US came into the war in December 1941 he transferred to the US army. After the war Fitzgibbon divided his time between London and his Irish property, making a living with writing and journalism. I’ve read some of his history and biography, it’s lively and makes no attempt at impartiality. I think his status as an Irishman in England gave him a particular angle in writing this book, a deep knowledge but a useful slight detachment. I think his class background and experience with living through the British resettlement of the forties led to this particular story, though I suspect the immediate impetus for it was the 1956 events of Suez, proving Britain’s political impotence in the wider world, and Hungary, demonstrating Soviet ruthlessness.

I think this book is meant not just as a warning but as a reminder. The text states outright that Britain isn’t Latvia or Tibet—he means his readers of the Cold War to consider what has happened to Latvia and Tibet, and as the Americans in the story abandon Britain to the USSR, he means the readers to consider that they have abandoned eastern Europe to it. If you read Orwell’s Collected Essays, Letters and Journalism, which I very much recommend, you can see Orwell in 1937 suggesting that people buy printing presses, because the day was coming when you wouldn’t be able to, and it would be useful to have one for producing samizdat. (He doesn’t call it that.) That day didn’t come, in Britain, but it did in eastern Europe, for the Czechs, the Hungarians, the Poles. When The Kissing Had To Stop is drawing a real parallel there, saying that Britain shouldn’t be comfortable and complacent when the gulags were real and Communism was dominating half the world. The real Russians weren’t much like Fitzgibbon’s Russians, the real world didn’t go his way, but the resolution in the UN in the book to protect the British way of life is modelled on the one brought before the UN in 1959 with reference to Tibet.

Jo Walton is a science fiction and fantasy writer. She’s published eight novels, most recently Half a Crown and Lifelode, and two poetry collections. She reads a lot, and blogs about it here regularly. She comes from Wales but lives in Montreal where the food and books are more varied.